Jefferson Ya Done Messed Up Again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jefferson-Monticello-illustration-1-631.jpg)

With five elementary words in the Declaration of Independence—"all men are created equal"—Thomas Jefferson undid Aristotle's ancient formula, which had governed human affairs until 1776: "From the hour of their nascency, some men are marked out for subjection, others for rule." In his original draft of the Declaration, in soaring, damning, fiery prose, Jefferson denounced the slave trade equally an "execrable commerce ...this assemblage of horrors," a "cruel war confronting man nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberties." Equally historian John Chester Miller put information technology, "The inclusion of Jefferson's strictures on slavery and the slave merchandise would take committed the United States to the abolition of slavery."

That was the way it was interpreted past some of those who read information technology at the fourth dimension as well. Massachusetts freed its slaves on the strength of the Declaration of Independence, weaving Jefferson'south linguistic communication into the state constitution of 1780. The significant of "all men" sounded as clear, and so disturbing to the authors of the constitutions of six Southern states that they emended Jefferson's wording. "All freemen," they wrote in their founding documents, "are equal." The authors of those state constitutions knew what Jefferson meant, and could not accept it. The Continental Congress ultimately struck the passage because Southward Carolina and Georgia, crying out for more slaves, would not bide shutting downwardly the market.

"Ane cannot question the genuineness of Jefferson's liberal dreams," writes historian David Brion Davis. "He was 1 of the first statesmen in whatever part of the world to advocate concrete measures for restricting and eradicating Negro slavery."

But in the 1790s, Davis continues, "the most remarkable thing near Jefferson'south stand up on slavery is his immense silence." And afterwards, Davis finds, Jefferson's emancipation efforts "virtually ceased."

Somewhere in a short span of years during the 1780s and into the early 1790s, a transformation came over Jefferson.

The very existence of slavery in the era of the American Revolution presents a paradox, and we have largely been content to leave it at that, since a paradox can offering a comforting state of moral suspended blitheness. Jefferson animates the paradox. And by looking closely at Monticello, we can see the procedure by which he rationalized an anathema to the point where an accented moral reversal was reached and he made slavery fit into America'southward national enterprise.

We can be forgiven if we interrogate Jefferson posthumously virtually slavery. Information technology is not judging him by today'southward standards to do and so. Many people of his ain fourth dimension, taking Jefferson at his word and seeing him equally the apotheosis of the country's highest ideals, appealed to him. When he evaded and rationalized, his admirers were frustrated and mystified; it felt like praying to a stone. The Virginia abolitionist Moncure Conway, noting Jefferson'southward indelible reputation as a would-exist emancipator, remarked scornfully, "Never did a man attain more fame for what he did non do."

Thomas Jefferson's mansion stands atop his mountain like the Platonic ideal of a business firm: a perfect creation existing in an ethereal realm, literally above the clouds. To achieve Monticello, you must arise what a company chosen "this steep, savage loma," through a thick wood and swirls of mist that recede at the superlative, every bit if past command of the master of the mountain. "If information technology had not been called Monticello," said i visitor, "I would call it Olympus, and Jove its occupant." The house that presents itself at the summit seems to incorporate some kind of secret wisdom encoded in its class. Seeing Monticello is like reading an old American Revolutionary manifesto—the emotions still rise. This is the compages of the New World, brought along by its guiding spirit.

In designing the mansion, Jefferson followed a precept laid downward 2 centuries earlier past Palladio: "Nosotros must contrive a building in such a manner that the finest and most noble parts of it be the most exposed to public view, and the less amusing disposed in by places, and removed from sight every bit much as possible."

The mansion sits atop a long tunnel through which slaves, unseen, hurried back and forth conveying platters of food, fresh tableware, ice, beer, wine and linens, while above them xx, 30 or twoscore guests sat listening to Jefferson's dinner-tabular array conversation. At 1 end of the tunnel lay the icehouse, at the other the kitchen, a hive of incessant activity where the enslaved cooks and their helpers produced i course after another.

During dinner Jefferson would open a panel in the side of the fireplace, insert an empty wine bottle and seconds after pull out a total canteen. We tin can imagine that he would delay explaining how this magic took place until an astonished guest put the question to him. The panel concealed a narrow dumbwaiter that descended to the basement. When Jefferson put an empty canteen in the compartment, a slave waiting in the basement pulled the dumbwaiter down, removed the empty, inserted a fresh bottle and sent it up to the main in a matter of seconds. Similarly, platters of hot nutrient magically appeared on a revolving door fitted with shelves, and the used plates disappeared from sight on the same dodge. Guests could not run across or hear any of the activity, nor the links between the visible world and the invisible that magically produced Jefferson's abundance.

Jefferson appeared every day at kickoff low-cal on Monticello's long terrace, walking alone with his thoughts. From his terrace Jefferson looked out upon an industrious, well-organized enterprise of black coopers, smiths, nailmakers, a brewer, cooks professionally trained in French cuisine, a glazier, painters, millers and weavers. Black managers, slaves themselves, oversaw other slaves. A squad of highly skilled artisans constructed Jefferson's coach. The household staff ran what was essentially a mid-sized hotel, where some 16 slaves waited upon the needs of a daily horde of guests.

The plantation was a small town in everything but proper noun, not merely considering of its size, but in its complexity. Skilled artisans and house slaves occupied cabins on Mulberry Row alongside hired white workers; a few slaves lived in rooms in the mansion'due south south dependency wing; some slept where they worked. Near of Monticello's slaves lived in clusters of cabins scattered downwards the mountain and on outlying farms. In his lifetime Jefferson owned more than 600 slaves. At any once about 100 slaves lived on the mountain; the highest slave population, in 1817, was 140.

Below the mansion there stood John Hemings' cabinetmaking shop, chosen the joinery, along with a dairy, a stable, a small fabric factory and a vast garden carved from the mountainside—the cluster of industries Jefferson launched to supply Monticello's household and bring in greenbacks. "To be independent for the comforts of life," Jefferson said, "nosotros must fabricate them ourselves." He was speaking of America's demand to develop manufacturing, but he had learned that truth on a microscale on his plantation.

Jefferson looked down from his terrace onto a customs of slaves he knew very well—an extended family unit and network of related families that had been in his ownership for two, iii or iv generations. Though there were several surnames among the slaves on the "mountaintop"—Fossett, Hern, Colbert, Gillette, Brown, Hughes—they were all Hemingses by blood, descendants of the matriarch Elizabeth "Betty" Hemings, or Hemings relatives past wedlock. "A peculiar fact virtually his house servants was that we were all related to one another," as a former slave recalled many years later. Jefferson's grandson Jeff Randolph observed, "Mr. Js Mechanics and his entire household of servants...consisted of i family connection and their wives."

For decades, archaeologists have been scouring Mulberry Row, finding mundane artifacts that testify to the fashion that life was lived in the workshops and cabins. They have plant saw blades, a large drill bit, an ax caput, blacksmith's pincers, a wall subclass fabricated in the joinery for a clock in the mansion, scissors, thimbles, locks and a primal, and finished nails forged, cut and hammered by nail boys.

The archaeologists also found a bundle of raw nail rod—a lost measure out of iron handed out to a nail boy one dawn. Why was this package found in the dirt, unworked, instead of forged, cut and hammered the way the dominate had told them? In one case, a missing bundle of rod had started a fight in the nailery that got one boy's skull bashed in and another sold southward to terrify the rest of the children—"in terrorem" were Jefferson'due south words—"as if he were put out of the way by death." Perhaps this very packet was the cause of the fight.

Weaving slavery into a narrative nigh Thomas Jefferson unremarkably presents a claiming to authors, just 1 writer managed to spin this vicious set on and terrible penalisation of a nailery male child into a charming plantation tale. In a 1941 biography of Jefferson for "young adults" (ages 12 to 16) the author wrote: "In this beehive of industry no discord or revilings found entrance: there were no signs of discontent on the black shining faces as they worked under the direction of their main....The women sang at their tasks and the children old enough to work made nails leisurely, not too overworked for a prank now and so."

It might seem unfair to mock the misconceptions and sappy prose of "a simpler era," except that this book, The Way of an Eagle, and hundreds similar it, shaped the attitudes of generations of readers about slavery and African-Americans. Fourth dimension magazine chose it every bit one of the "important books" of 1941 in the children'south literature category, and it gained a second life in America'southward libraries when information technology was reprinted in 1961 as Thomas Jefferson: Fighter for Freedom and Human Rights.

In describing what Mulberry Row looked like, William Kelso, the archaeologist who excavated it in the 1980s, writes, "There can be little doubtfulness that a relatively shabby Primary Street stood there." Kelso notes that "throughout Jefferson's tenure, it seems safe to conclude that the spartan Mulberry Row buildings...made a jarring impact on the Monticello landscape."

It seems puzzling that Jefferson placed Mulberry Row, with its slave cabins and piece of work buildings, so shut to the mansion, simply we are projecting the present onto the by. Today, tourists tin walk freely up and downward the onetime slave quarter. Simply in Jefferson'south fourth dimension, guests didn't go there, nor could they meet it from the mansion or the lawn. Only one visitor left a description of Mulberry Row, and she got a glimpse of it merely considering she was a close friend of Jefferson's, someone who could exist counted upon to look with the right attitude. When she published her business relationship in the Richmond Enquirer, she wrote that the cabins would appear "poor and uncomfortable" but to people of "northern feelings."

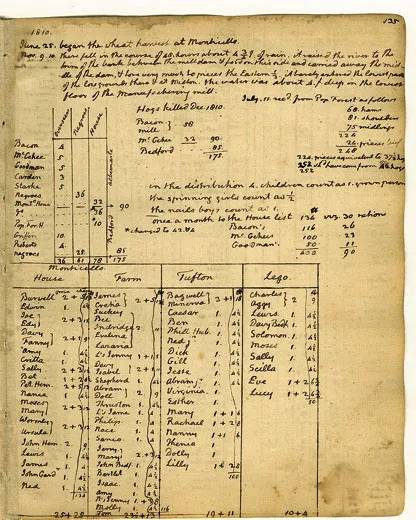

The critical turning point in Jefferson'southward thinking may well have come in 1792. As Jefferson was counting up the agricultural profits and losses of his plantation in a letter to President Washington that year, it occurred to him that there was a phenomenon he had perceived at Monticello but never really measured. He proceeded to summate it in a barely legible, scribbled note in the heart of a folio, enclosed in brackets. What Jefferson prepare out clearly for the first fourth dimension was that he was making a iv percent profit every year on the birth of black children. The enslaved were yielding him a bonanza, a perpetual human dividend at compound interest. Jefferson wrote, "I allow zippo for losses by expiry, but, on the reverse, shall soon take credit iv per cent. per annum, for their increase over and above keeping up their own numbers." His plantation was producing inexhaustible homo avails. The percentage was predictable.

In another communication from the early 1790s, Jefferson takes the 4 percent formula further and quite bluntly advances the notion that slavery presented an investment strategy for the future. He writes that an associate who had suffered fiscal reverses "should have been invested in negroes." He advises that if the friend'southward family had any greenbacks left, "every farthing of information technology [should be] laid out in state and negroes, which too a present support bring a silent profit of from 5. to x. per cent in this state by the increase in their value."

The irony is that Jefferson sent his iv percent formula to George Washington, who freed his slaves, precisely considering slavery had made homo beings into coin, like "Cattle in the marketplace," and this disgusted him. Yet Jefferson was correct, prescient, about the investment value of slaves. A startling statistic emerged in the 1970s, when economists taking a hardheaded await at slavery institute that on the eve of the Civil War, enslaved blackness people, in the aggregate, formed the 2d most valuable capital asset in the United States. David Brion Davis sums upward their findings: "In 1860, the value of Southern slaves was about three times the amount invested in manufacturing or railroads nationwide." The simply asset more valuable than the black people was the land itself. The formula Jefferson had stumbled upon became the engine not only of Monticello but of the unabridged slaveholding Southward and the Northern industries, shippers, banks, insurers and investors who weighed risk against returns and bet on slavery. The words Jefferson used—"their increment"—became magic words.

Jefferson's four percent theorem threatens the comforting notion that he had no real sensation of what he was doing, that he was "stuck" with or "trapped" in slavery, an obsolete, unprofitable, burdensome legacy. The date of Jefferson's calculation aligns with the waning of his emancipationist fervor. Jefferson began to dorsum away from antislavery just around the time he computed the silent turn a profit of the "peculiar institution."

And this globe was crueler than we have been led to believe. A letter of the alphabet has recently come to calorie-free describing how Monticello's young black boys, "the small ones," age 10, 11 or 12, were whipped to get them to work in Jefferson'south blast factory, whose profits paid the mansion's grocery bills. This passage almost children being lashed had been suppressed—deliberately deleted from the published record in the 1953 edition of Jefferson's Farm Book, containing 500 pages of plantation papers. That edition of the Farm Book still serves as a standard reference for research into the way Monticello worked.

By 1789, Jefferson planned to shift away from growing tobacco at Monticello, whose cultivation he described as "a civilization of infinite wretchedness." Tobacco wore out the soil so fast that new acreage constantly had to be cleared, engrossing so much land that food could not be raised to feed the workers and requiring the farmer to purchase rations for the slaves. (In a strangely modernistic twist, Jefferson had taken annotation of the measurable climate change in the region: The Chesapeake region was unmistakably cooling and becoming inhospitable to heat-loving tobacco that would soon, he thought, get the staple of South Carolina and Georgia.) He visited farms and inspected equipment, considering a new crop, wheat, and the exciting prospect it opened before him.

The cultivation of wheat revitalized the plantation economy and reshaped the South'southward agricultural landscape. Planters all over the Chesapeake region had been making the shift. (George Washington had begun raising grains some thirty years earlier because his state wore out faster than Jefferson'south did.) Jefferson continued to plant some tobacco because it remained an of import cash crop, but his vision for wheat farming was rapturous: "The cultivation of wheat is the reverse [of tobacco] in every circumstance. As well cloathing the earth with herbage, and preserving its fertility, it feeds the labourers plentifully, requires from them only a moderate toil, except in the season of harvest, raises groovy numbers of animals for nutrient and service, and diffuses enough and happiness amongst the whole."

Wheat farming forced changes in the human relationship between planter and slave. Tobacco was raised by gangs of slaves all doing the same repetitive, backbreaking tasks under the straight, strict supervision of overseers. Wheat required a variety of skilled laborers, and Jefferson's ambitious plans required a retrained piece of work forcefulness of millers, mechanics, carpenters, smiths, spinners, coopers, and plowmen and plowmen.

Jefferson however needed a cohort of "labourers in the ground" to deport out the hardest tasks, so the Monticello slave community became more segmented and hierarchical. They were all slaves, just some slaves would exist meliorate than others. The bulk remained laborers; above them were enslaved artisans (both male person and female); to a higher place them were enslaved managers; above them was the household staff. The higher you stood in the hierarchy, the better clothes and nutrient you lot got; you also lived literally on a college plane, closer to the mountaintop. A small minority of slaves received pay, profit sharing or what Jefferson chosen "gratuities," while the lowest workers received just the barest rations and wear. Differences bred resentment, specially toward the elite household staff.

Planting wheat required fewer workers than tobacco, leaving a pool of field laborers available for specialized training. Jefferson embarked on a comprehensive plan to modernize slavery, diversify it and industrialize it. Monticello would have a nail mill, a cloth mill, a curt-lived tinsmithing performance, coopering and charcoal burning. He had ambitious plans for a flour mill and a canal to provide water power for it.

Grooming for this new organization began in childhood. Jefferson sketched out a plan in his Subcontract Book: "children till x. years sometime to serve as nurses. from x. to sixteen. the boys make nails, the girls spin. at 16. get into the basis or learn trades."

Tobacco required child labor (the small stature of children made them ideal workers for the distasteful chore of plucking and killing tobacco worms); wheat did not, and then Jefferson transferred his surplus of immature workers to his nail factory (boys) and spinning and weaving operations (girls).

He launched the nailery in 1794 and supervised information technology personally for three years. "I now employ a dozen little boys from ten. to sixteen. years of age, overlooking all the details of their business myself." He said he spent half the day counting and measuring nails. In the morning time he weighed and distributed nail rod to each nailer; at the end of the day he weighed the finished production and noted how much rod had been wasted.

The nailery "particularly suited me," he wrote, "considering it would employ a parcel of boys who would otherwise exist idle." Equally important, information technology served as a preparation and testing basis. All the nail boys got actress food; those who did well received a new conform of apparel, and they could also expect to graduate, as information technology were, to training equally artisans rather than going "in the footing" as common field slaves.

Some nail boys rose in the plantation hierarchy to become firm servants, blacksmiths, carpenters or coopers. Wormley Hughes, a slave who became head gardener, started in the nailery, as did Burwell Colbert, who rose to become the mansion's butler and Jefferson's personal attendant. Isaac Granger, the son of an enslaved Monticello foreman, Great George Granger, was the most productive nailer, with a profit averaging 80 cents a day over the first half dozen months of 1796, when he was 20; he fashioned half a ton of nails during those six months. The piece of work was deadening in the farthermost. Confined for long hours in the hot, smoky workshop, the boys hammered out 5,000 to 10,000 nails a day, producing a gross income of $2,000 in 1796. Jefferson's contest for the nailery was the land penitentiary.

The nailers received twice the nutrient ration of a field worker but no wages. Jefferson paid white boys (an overseer'south sons) l cents a twenty-four hours for cutting forest to feed the nailery'southward fires, only this was a weekend job done "on Saturdays, when they were not in school."

Exuberant over the success of the nailery, Jefferson wrote: "My new trade of blast-making is to me in this country what an additional title of dignity or the ensigns of a new order are in Europe." The profit was substantial. Just months after the mill began operation, he wrote that "a nailery which I have established with my own negro boys now provides completely for the maintenance of my family." 2 months of labor by the nail boys paid the entire almanac grocery bill for the white family. He wrote to a Richmond merchant, "My groceries come up to betwixt iv. and 500. Dollars a yr, taken and paid for quarterly. The best resources of quarterly paiment in my power is Nails, of which I brand enough every fortnight [emphasis added] to pay a quarter's nib."

In an 1840s memoir, Isaac Granger, past and then a freedman who had taken the surname Jefferson, recalled circumstances at the nailery. Isaac, who worked there as a immature homo, specified the incentives that Jefferson offered to nailers: "Gave the boys in the nail factory a pound of meat a week, a dozen herrings, a quart of molasses, and peck of meal. Requite them that wukked the best a suit of cherry-red or bluish; encouraged them mightily." Non all the slaves felt so mightily encouraged. It was Great George Granger's job, as foreman, to get those people to work. Without molasses and suits to offer, he had to rely on persuasion, in all its forms. For years he had been very successful—by what methods, we don't know. But in the winter of 1798 the system footing to a halt when Granger, peradventure for the first time, refused to whip people.

Col. Thomas Mann Randolph, Jefferson's son-in-law, reported to Jefferson, then living in Philadelphia as vice president, that "insubordination" had "greatly clogged" operations under Granger. A month later there was "progress," only Granger was "absolutely wasting with care." He was defenseless between his own people and Jefferson, who had rescued the family when they had been sold from the plantation of Jefferson'due south male parent-in-constabulary, given him a good job, allowed him to earn money and own property, and shown similar benevolence to Granger'south children. Now Jefferson had his heart on Granger's output.

Jefferson noted curtly in a letter to Randolph that another overseer had already delivered his tobacco to the Richmond market, "where I promise George's will before long bring together information technology." Randolph reported back that Granger's people had not even packed the tobacco yet, but gently urged his father-in-police to have patience with the foreman: "He is not devil-may-care...tho' he procrastinates too much." It seems that Randolph was trying to protect Granger from Jefferson's wrath. George was not procrastinating; he was struggling confronting a workforce that resisted him. Only he would not beat them, and they knew it.

At length, Randolph had to admit the truth to Jefferson. Granger, he wrote, "cannot control his force." The only recourse was the whip. Randolph reported "instances of disobedience so gross that I am obliged to interfere and have them punished myself." Randolph would not have administered the whip personally; they had professionals for that.

About probable he chosen in William Page, the white overseer who ran Jefferson's farms beyond the river, a homo notorious for his cruelty. Throughout Jefferson'south plantation records there runs a thread of indicators—some direct, some oblique, some euphemistic—that the Monticello machine operated on carefully calibrated brutality. Some slaves would never readily submit to bondage. Some, Jefferson wrote, "require a vigour of discipline to make them practise reasonable work." That plain argument of his policy has been largely ignored in preference to Jefferson'south well-known self-exoneration: "I love industry and abhor severity." Jefferson made that reassuring remark to a neighbor, but he might as well have been talking to himself. He hated disharmonize, disliked having to punish people and found ways to distance himself from the violence his system required.

Thus he went on tape with a denunciation of overseers as "the virtually abject, degraded and unprincipled race," men of "pride, insolence and spirit of domination." Though he despised these brutes, they were hardhanded men who got things done and had no misgivings. He hired them, issuing orders to impose a vigor of discipline.

It was during the 1950s, when historian Edwin Betts was editing one of Colonel Randolph's plantation reports for Jefferson's Farm Book, that he confronted a taboo subject and fabricated his fateful deletion. Randolph reported to Jefferson that the nailery was performance very well considering "the pocket-sized ones" were beingness whipped. The youngsters did non accept willingly to being forced to show upward in the icy midwinter hour before dawn at the chief's nail forge. And then the overseer, Gabriel Lilly, was whipping them "for truancy."

Betts decided that the epitome of children being browbeaten at Monticello had to exist suppressed, omitting this document from his edition. He had an entirely different image in his caput; the introduction to the book alleged, "Jefferson came close to creating on his own plantations the ideal rural community." Betts couldn't do anything nearly the original letter of the alphabet, but no one would see it, tucked abroad in the athenaeum of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The full text did not sally in print until 2005.

Betts' omission was important in shaping the scholarly consensus that Jefferson managed his plantations with a lenient mitt. Relying on Betts' editing, the historian Jack McLaughlin noted that Lilly "resorted to the whip during Jefferson'south absenteeism, just Jefferson put a terminate to it."

"Slavery was an evil he had to alive with," historian Merrill Peterson wrote, "and he managed it with what little dosings of humanity a diabolical arrangement permitted." Peterson echoed Jefferson's complaints about the work forcefulness, alluding to "the slackness of slave labor," and emphasized Jefferson'southward benevolence: "In the direction of his slaves Jefferson encouraged diligence but was instinctively too lenient to demand information technology. Past all accounts he was a kind and generous primary. His conviction of the injustice of the establishment strengthened his sense of obligation toward its victims."

Joseph Ellis observed that only "on rare occasions, and as a last resort, he ordered overseers to use the lash." Dumas Malone stated, "Jefferson was kind to his servants to the point of indulgence, and within the framework of an institution he disliked he saw that they were well provided for. His 'people' were devoted to him."

As a rule, the slaves who lived at the mountaintop, including the Hemings family unit and the Grangers, were treated better than slaves who worked the fields farther down the mount. But the machine was hard to restrain.

After the violent tenures of earlier overseers, Gabriel Lilly seemed to portend a gentler reign when he arrived at Monticello in 1800. Colonel Randolph's commencement report was optimistic. "All goes well," he wrote, and "what is under Lillie admirably." His second report almost two weeks afterwards was glowing: "Lillie goes on with great spirit and complete quiet at Mont'o.: he is so good tempered that he tin go twice equally much washed without the smallest discontent as some with the hardest driving possible." In addition to placing him over the laborers "in the ground" at Monticello, Jefferson put Lilly in charge of the nailery for an extra fee of £x a year.

One time Lilly established himself, his adept atmosphere plainly evaporated, considering Jefferson began to worry about what Lilly would do to the nailers, the promising adolescents whom Jefferson managed personally, intending to move them up the plantation ladder. He wrote to Randolph: "I forgot to ask the favor of yous to speak to Lilly as to the treatment of the nailers. it would destroy their value in my estimation to dethrone them in their own eyes past the whip. this therefore must not be resorted to merely in extremities. as they volition once more exist under my government, I would chuse they should retain the stimulus of character." Merely in the same letter he emphasized that output must be maintained: "I hope Lilly keeps the pocket-size nailers engaged and so as to supply our customers."

Colonel Randolph immediately dispatched a reassuring simply advisedly worded reply: "Everything goes well at Mont'o.—the Nailers all [at] work and executing well some heavy orders. ...I had given a charge of lenity respecting all: (Burwell absolutely excepted from the whip alltogether) before you lot wrote: none have incurred it but the small ones for truancy." To the news that the small ones were being whipped and that "lenity" had an rubberband meaning, Jefferson had no response; the pocket-size ones had to exist kept "engaged."

It seems that Jefferson grew uneasy about Lilly's authorities at the nailery. Jefferson replaced him with William Stewart but kept Lilly in charge of the adult crews building his mill and culvert. Under Stewart's lenient control (greatly softened by habitual drinking), the nailery'south productivity sank. The nail boys, favored or not, had to exist brought to heel. In a very unusual alphabetic character, Jefferson told his Irish master joiner, James Dinsmore, that he was bringing Lilly back to the nailery. It might seem puzzling that Jefferson would feel compelled to explicate a personnel determination that had nothing to exercise with Dinsmore, simply the nailery stood simply a few steps from Dinsmore's shop. Jefferson was preparing Dinsmore to witness scenes nether Lilly's command such as he had non seen under Stewart, and his tone was stern: "I am quite at a loss near the nailboys remaining with mr Stewart. they have long been a dead expence instead of profit to me. in truth they require a vigour of bailiwick to make them do reasonable work, to which he cannot bring himself. on the whole I think it volition be best for them as well to be removed to mr Lilly's [control]."

The incident of horrible violence in the nailery—the assail past i nail boy against another—may shed some lite on the fear Lilly instilled in the nail boys. In 1803 a nailer named Cary smashed his hammer into the skull of a fellow nailer, Brown Colbert. Seized with convulsions, Colbert went into a coma and would certainly have died had Colonel Randolph not immediately summoned a doc, who performed brain surgery. With a trephine saw, the doctor drew back the cleaved part of Colbert'south skull, thus relieving pressure level on the brain. Amazingly, the immature man survived.

Bad plenty that Cary had and so viciously attacked someone, but his victim was a Hemings. Jefferson angrily wrote to Randolph that "it will be necessary for me to brand an example of him in terrorem to others, in guild to maintain the police so rigorously necessary amid the nail boys." He ordered that Cary exist sold away "so distant as never more than to be heard of amid usa." And he alluded to the abyss beyond the gates of Monticello into which people could be flung: "There are generally negro purchasers from Georgia passing about the state." Randolph's written report of the incident included Cary's motive: The boy was "irritated at some little trick from Brown, who hid part of his nailrod to teaze him." But under Lilly's regime this fox was not so "little." Colbert knew the rules, and he knew very well that if Cary couldn't discover his nailrod, he would fall behind, and nether Lilly that meant a beating. Hence the furious assault.

Jefferson's daughter Martha wrote to her father that one of the slaves, a ill-behaved and confusing man named John, tried to poison Lilly, perchance hoping to kill him. John was safe from any severe penalisation because he was a hired slave: If Lilly injured him, Jefferson would have to compensate his possessor, and then Lilly had no means to retaliate. John, evidently grasping the extent of his amnesty, took every opportunity to undermine and provoke him, even "cutting upwardly [Lilly's] garden [and] destroying his things."

But Lilly had his own kind of amnesty. He understood his importance to Jefferson when he renegotiated his contract, so that commencement in 1804 he would no longer receive a flat fee for managing the nailery only exist paid 2 percent of the gross. Productivity immediately soared. In the spring of 1804, Jefferson wrote to his supplier: "The manager of my nailery had and so increased its activity as to call for a larger supply of rod...than had heretofore been necessary."

Maintaining a high level of activity required a commensurate level of subject. Thus, in the autumn of 1804, when Lilly was informed that one of the nail boys was sick, he would have none of it. Appalled by what happened next, one of Monticello's white workmen, a carpenter named James Oldham, informed Jefferson of "the Boorishness that [Lilly] fabricated apply of with Little Jimmy."

Oldham reported that James Hemings, the 17-twelvemonth-old son of the house retainer Critta Hemings, had been sick for iii nights running, so sick that Oldham feared the male child might not alive. He took Hemings into his own room to keep lookout man over him. When he told Lilly that Hemings was seriously ill, Lilly said he would whip Jimmy into working. Oldham "begged him not to punish him," but "this had no effect." The "Barbarity" ensued: Lilly "whipped him three times in one twenty-four hours, and the boy was really not able to raise his hand to his head."

Flogging to this degree does not persuade someone to piece of work; information technology disables him. Simply it also sends a message to the other slaves, especially those, like Jimmy, who belonged to the elite class of Hemings servants and might think they were higher up the authority of Gabriel Lilly. In one case he recovered, Jimmy Hemings fled Monticello, joining the customs of complimentary blacks and runaways who fabricated a living as boatmen on the James River, floating up and down betwixt Richmond and obscure backwater villages. Contacting Hemings through Oldham, Jefferson tried to persuade him to come home, simply did not set the slave catchers after him. There is no record that Jefferson fabricated any remonstrance against Lilly, who was unrepentant virtually the chirapsia and loss of a valuable slave; indeed, he demanded that his salary be doubled to £100. This put Jefferson in a quandary. He displayed no misgivings near the regime that Oldham characterized as "the most cruel," only £100 was more than he wanted to pay. Jefferson wrote that Lilly as an overseer "is every bit skilful a ane every bit tin be"—"certainly I can never get a man who fulfills my purposes better than he does."

On a recent afternoon at Monticello, Fraser Neiman, the head archaeologist, led the way downwardly the mount into a ravine, following the trace of a road laid out by Jefferson for his carriage rides. It passed the house of Edmund Bacon, the overseer Jefferson employed from 1806 to 1822, about a mile from the mansion. When Jefferson retired from the presidency in 1809, he moved the nailery from the summit—he no longer wanted even to see information technology, let alone manage information technology—to a site downhill 100 yards from Bacon's business firm. The archaeologists discovered unmistakable testify of the store—nails, nail rod, charcoal, coal and slag. Neiman pointed out on his map locations of the shop and Bacon's firm. "The nailery was a socially fractious place," he said. "One suspects that'due south role of the reason for getting it off the mountaintop and putting it correct here next to the overseer'due south house."

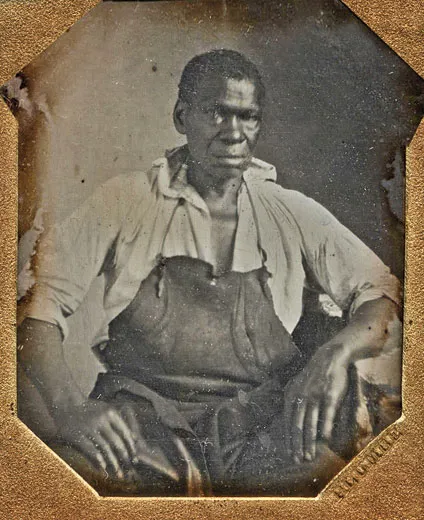

About 600 feet e of Salary'southward house stood the cabin of James Hubbard, a slave who lived past himself. The archaeologists dug more than 100 test pits at this site but came up with nothing; nonetheless, when they brought in metal detectors and turned up a few wrought nails, information technology was plenty evidence to convince them that they had constitute the actual site of Hubbard'due south firm. Hubbard was 11 years old and living with his family at Poplar Wood, Jefferson'southward second plantation, near Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1794, when Jefferson brought him to Monticello to work in the new nailery on the mountaintop. His assignment was a sign of Jefferson'south favor for the Hubbard family. James' father, a skilled shoemaker, had risen to the mail of foreman of labor at Poplar Forest; Jefferson saw similar potential in the son. At first James performed abysmally, wasting more material than any of the other nail boys. Maybe he was merely a slow learner; perhaps he hated it; but he made himself better and better at the miserable work, swinging his hammer thousands of times a solar day, until he excelled. When Jefferson measured the nailery'southward output he found that Hubbard had reached the height—90 percent efficiency—in converting nail rod to finished nails.

A model slave, eager to improve himself, Hubbard grasped every opportunity the arrangement offered. In his fourth dimension off from the nailery, he took on additional tasks to earn cash. He sacrificed slumber to make money by burning charcoal, tending a kiln through the dark. Jefferson also paid him for hauling—a position of trust considering a homo with a horse and permission to leave the plantation could easily escape. Through his industriousness Hubbard laid aside plenty cash to purchase some fine apparel, including a hat, knee breeches and two overcoats.

Then 1 day in the summertime of 1805, early in Jefferson'south 2nd term equally president, Hubbard vanished. For years he had patiently carried out an elaborate deception, pretending to exist the loyal, hardworking slave. He had done that hard work non to soften a life in slavery but to escape it. The clothing was non for show; it was a disguise.

Hubbard had been gone for many weeks when the president received a letter from the sheriff of Fairfax Canton. He had in custody a man named Hubbard who had confessed to being an escaped slave. In his confession Hubbard revealed the details of his escape. He had made a bargain with Wilson Lilly, son of the overseer Gabriel Lilly, paying him $5 and an overcoat in exchange for false emancipation documents and a travel laissez passer to Washington. Merely illiteracy was Hubbard's downfall: He did non realize that the documents Wilson Lilly had written were not very persuasive. When Hubbard reached Fairfax Canton, most 100 miles due north of Monticello, the sheriff stopped him, demanding to run across his papers. The sheriff, who knew forgeries when he saw them and arrested Hubbard, also asked Jefferson for a reward because he had run "a smashing Risk" arresting "every bit large a fellow every bit he is."

Hubbard was returned to Monticello. If he received some punishment for his escape, there is no record of it. In fact, information technology seems that Hubbard was forgiven and regained Jefferson's trust inside a year. The October 1806 schedule of work for the nailery shows Hubbard working with the heaviest gauge of rod with a daily output of 15 pounds of nails. That Christmas, Jefferson immune him to travel from Monticello to Poplar Wood to see his family. Jefferson may have trusted him again, but Bacon remained wary.

One 24-hour interval when Bacon was trying to fill up an order for nails, he institute that the entire stock of eight-penny nails—300 pounds of nails worth $50—was gone: "Of course they had been stolen." He immediately suspected James Hubbard and confronted him, but Hubbard "denied information technology powerfully." Bacon ransacked Hubbard's cabin and "every place I could remember of" but came upward empty-handed. Despite the lack of evidence, Bacon remained convinced of Hubbard's guilt. He conferred with the white managing director of the nailery, Reuben Grady: "Let the states drop information technology. He has hid them somewhere, and if nosotros say no more most information technology, we shall find them."

Walking through the woods after a heavy rain, Bacon spotted dingy tracks on the leaves on i side of the path. He followed the tracks to their end, where he found the nails buried in a big box. Immediately, he went up the mountain to inform Jefferson of the discovery and of his certainty that Hubbard was the thief. Jefferson was "very much surprised and felt very badly nearly information technology" because Hubbard "had always been a favorite retainer." Jefferson said he would question Hubbard personally the adjacent forenoon when he went on his usual ride past Salary's business firm.

When Jefferson showed up the adjacent mean solar day, Salary had Hubbard called in. At the sight of his primary, Hubbard burst into tears. Salary wrote, "I never saw any person, white or black, feel as badly as he did when he saw his main. He was mortified and distressed beyond measure....[West]e all had confidence in him. Now his character was gone." Hubbard tearfully begged Jefferson's pardon "over and over again." For a slave, burglary was a capital crime. A runaway slave who once broke into Bacon'due south private storehouse and stole three pieces of salary and a bag of cornmeal was condemned to hang in Albemarle County. The governor commuted his sentence, and the slave was "transported," the legal term for existence sold past the state to the Deep South or West Indies.

Even Bacon felt moved past Hubbard's plea—"I felt very desperately myself"— but he knew what would come next: Hubbard had to be whipped. So Bacon was astonished when Jefferson turned to him and said, "Ah, sir, we can't punish him. He has suffered enough already." Jefferson offered some counsel to Hubbard, "gave him a heap of practiced advice," and sent him back to the nailery, where Reuben Grady was waiting, "expecting ...to whip him."

Jefferson's magnanimity seemed to spark a conversion in Hubbard. When he got to the nailery, he told Grady he'd been seeking religion for a long time, "but I never heard anything before that sounded and so, or fabricated me feel so, as I did when master said, 'Go, and don't do and so whatever more.' " So now he was "determined to seek faith till I find it." Bacon said, "Sure enough, he afterwards came to me for a permit to go and be baptized." But that, also, was charade. On his authorized absences from the plantation to nourish church, Hubbard made arrangements for another escape.

During the holiday season in late 1810, Hubbard vanished over again. Documents about Hubbard's escape reveal that Jefferson's plantations were riven with secret networks. Jefferson had at least one spy in the slave community willing to inform on beau slaves for cash; Jefferson wrote that he "engaged a trusty negro man of my own, and promised him a reward...if he could inform usa and so that [Hubbard] should be taken." But the spy could not get anyone to talk. Jefferson wrote that Hubbard "has not been heard of." Only that was non truthful: a few people had heard of Hubbard's movements.

Jefferson could not crack the wall of silence at Monticello, but an informer at Poplar Forest told the overseer that a boatman belonging to Colonel Randolph aided Hubbard's escape, clandestinely ferrying him upward the James River from Poplar Forest to the area around Monticello, even though white patrollers of 2 or three counties were hunting the fugitive. The boatman might have been part of a network that plied the Rivanna and James rivers, smuggling appurtenances and fugitives.

Peradventure, Hubbard tried to make contact with friends effectually Monticello; possibly, he was planning to flee to the North again; possibly, it was all disinformation planted by Hubbard's friends. At some point Hubbard headed southwest, not north, across the Blue Ridge. He made his way to the town of Lexington, where he was able to alive for over a year as a free homo, being in possession of an impeccable manumission document.

His description appeared in the Richmond Enquirer: "a Nailor by trade, of 27 years of historic period, virtually half dozen anxiety high, stout limbs and strong made, of daring demeanor, bold and harsh features, nighttime complexion, apt to beverage freely and had even furnished himself with money and probably a costless laissez passer; on a onetime elopement he attempted to get out of the State Northwardly . . . and probably may accept taken the same direction now."

A twelvemonth later on his escape Hubbard was spotted in Lexington. Before he could be captured, he took off again, heading farther west into the Allegheny Mountains, simply Jefferson put a slave tracker on his trail. Cornered and clapped in irons, Hubbard was brought dorsum to Monticello, where Jefferson made an example of him: "I had him severely flogged in the presence of his sometime companions, and committed to jail." Under the lash Hubbard revealed the details of his escape and the proper name of an accomplice; he had been able to elude capture past carrying 18-carat manumission papers he'd bought from a costless black human being in Albemarle County. The man who provided Hubbard with the papers spent six months in jail. Jefferson sold Hubbard to 1 of his overseers, and his final fate is not known.

Slaves lived as if in an occupied country. As Hubbard discovered, few could outrun the newspaper ads, slave patrols, vigilant sheriffs demanding papers and slave-communicable compensation hunters with their guns and dogs. Hubbard was brave or drastic enough to try it twice, unmoved past the incentives Jefferson held out to cooperative, diligent, industrious slaves.

In 1817, Jefferson's old friend, the Revolutionary War hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko, died in Switzerland. The Polish nobleman, who had arrived from Europe in 1776 to aid the Americans, left a substantial fortune to Jefferson. Kosciuszko bequeathed funds to free Jefferson'south slaves and purchase land and farming equipment for them to begin a life on their own. In the leap of 1819, Jefferson pondered what to exercise with the legacy. Kosciuszko had made him executor of the volition, then Jefferson had a legal duty, besides equally a personal obligation to his deceased friend, to bear out the terms of the certificate.

The terms came as no surprise to Jefferson. He had helped Kosciuszko draft the will, which states, "I hereby authorize my friend, Thomas Jefferson, to employ the whole [bequest] in purchasing Negroes from his ain or whatsoever others and giving them liberty in my proper name." Kosciuszko'southward estate was almost $20,000, the equivalent today of roughly $280,000. But Jefferson refused the gift, fifty-fifty though it would take reduced the debt hanging over Monticello, while too relieving him, in part at least, of what he himself had described in 1814 every bit the "moral reproach" of slavery.

If Jefferson had accepted the legacy, as much as half of it would have gone not to Jefferson simply, in issue, to his slaves—to the purchase price for land, livestock, equipment and transportation to institute them in a place such as Illinois or Ohio. Moreover, the slaves about suited for immediate emancipation—smiths, coopers, carpenters, the nigh skilled farmers—were the very ones whom Jefferson nearly valued. He also shrank from any public identification with the cause of emancipation.

Information technology had long been accustomed that slaves were assets that could be seized for debt, but Jefferson turned this around when he used slaves as collateral for a very big loan he had taken out in 1796 from a Dutch banking house in order to rebuild Monticello. He pioneered the monetizing of slaves, just equally he pioneered the industrialization and diversification of slavery.

Before his refusal of Kosciuszko'south legacy, as Jefferson mulled over whether to accept the heritance, he had written to i of his plantation managers: "A child raised every 2. years is of more profit then the ingather of the best laboring homo. in this, every bit in all other cases, providence has made our duties and our interests coincide perfectly.... [W]ith respect therefore to our women & their children I must pray you lot to inculcate upon the overseers that it is not their labor, merely their increase which is the first consideration with us."

In the 1790s, every bit Jefferson was mortgaging his slaves to build Monticello, George Washington was trying to scrape together financing for an emancipation at Mountain Vernon, which he finally ordered in his will. He proved that emancipation was not only possible, but applied, and he overturned all the Jeffersonian rationalizations. Jefferson insisted that a multiracial society with free black people was impossible, only Washington did non remember so. Never did Washington suggest that blacks were inferior or that they should exist exiled.

It is curious that we accept Jefferson as the moral standard of the founders' era, not Washington. Perchance it is because the Male parent of his Country left a somewhat troubling legacy: His emancipation of his slaves stands as not a tribute just a rebuke to his era, and to the prevaricators and profiteers of the hereafter, and declares that if you lot claim to have principles, y'all must live past them.

After Jefferson's death in 1826, the families of Jefferson's nearly devoted servants were separate autonomously. Onto the auction cake went Caroline Hughes, the 9-year-old girl of Jefferson's gardener Wormley Hughes. One family was divided upwards among eight different buyers, another family among seven buyers.

Joseph Fossett, a Monticello blacksmith, was amidst the handful of slaves freed in Jefferson'due south will, but Jefferson left Fossett'southward family enslaved. In the half-dozen months between Jefferson'due south decease and the sale of his property, Fossett tried to strike bargains with families in Charlottesville to purchase his wife and six of his seven children. His oldest child (born, ironically, in the White House itself) had already been given to Jefferson's grandson. Fossett found sympathetic buyers for his married woman, his son Peter and two other children, but he watched the sale of 3 young daughters to different buyers. One of them, 17-year-old Patsy, immediately escaped from her new main, a Academy of Virginia official.

Joseph Fossett spent ten years at his anvil and forge earning the coin to buy back his wife and children. Past the tardily 1830s he had cash in mitt to reclaim Peter, then about 21, only the owner reneged on the deal. Compelled to go out Peter in slavery and having lost three daughters, Joseph and Edith Fossett departed Charlottesville for Ohio around 1840. Years afterwards, speaking as a free man in Ohio in 1898, Peter, who was 83, would recount that he had never forgotten the moment when he was "put upwardly on the sale cake and sold like a horse."

The Smithsonian Book of Presidential Trivia

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-dark-side-of-thomas-jefferson-35976004/

0 Response to "Jefferson Ya Done Messed Up Again"

Post a Comment